Nigeria boasts the largest population on the African continent – one of the fastest-growing in the world.1 And, with over 40% of its residents under the age of 15, laying the foundation for a healthy society is vital to the country’s future.2

The endemic burden of soil-transmitted helminths (STH) in Nigeria impairs the physical health and well-being of millions of children today and foreshadows a cycle of negative consequences for individuals, communities, and society as a whole. According to the World Health Organization, nearly 17 million Nigerian preschool-aged children are eligible to receive Albendazole for deworming.3 However, no current data exists to indicate just how many children in this age group are being reached through national efforts.4 If the 2020 coverage rate for school-aged children (69%) is any indicator, gaps in coverage exist.5

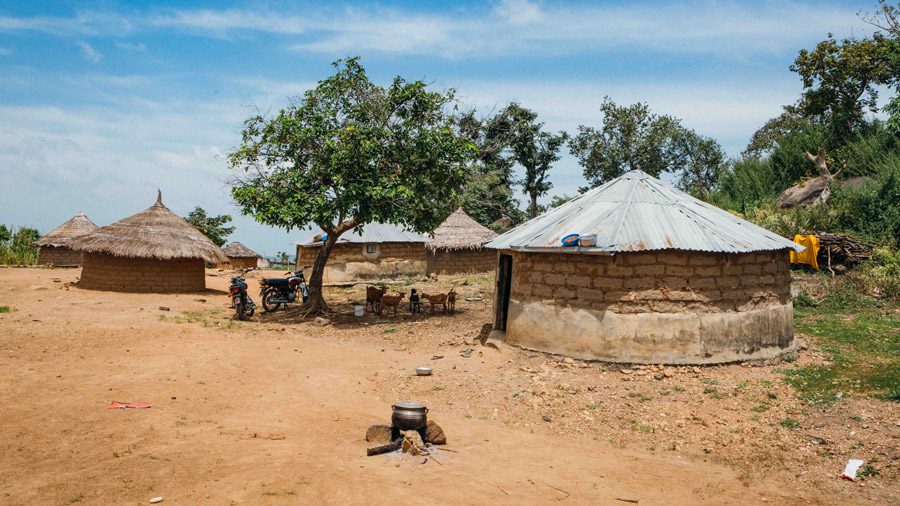

Poor housing conditions for low-income and rural communities predispose individuals to an increased risk of malnutrition and contracting infectious diseases, including STH. According to a representative from Ramberg Child Survival Initiative (RACSI), an NGO based in Makurdi, Nigeria, water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) measures are inadequate. In RACSI’s service areas, individuals experience “unsatisfactory environmental sanitation (i.e., open defecation)” and water and food-associated pollution, coupled with limited or no education on the importance of hand-washing and other preventative actions.

Poor infrastructure and low awareness of solutions are only some of the barriers Nigerian children experience in obtaining optimal health, “most of the problems and needs of rural areas are multifactorial in origin and require multidisciplinary interventions.”

Lack of access resulting from the “uneven distribution of health services and the shortage of physicians, nurses, and trained health personnel in rural areas” contributes to “high mortality and low average life expectancy,” according to RACSI. Similarly, “the perception of poor quality, and inadequacy of available services,” often dissuades individuals who want or need care from obtaining it. In addition, “Mothers most times don’t take their children to the facilities; they prefer services to be taken to them at the household level.”

However, just as the obstacles to care are complex, the solutions RACSI offers to overcome them are too. For example, RACSI developed community-based teams of staff and volunteers who operate at the local level. To foster behavioral change, these teams conduct outreach and home visits that promote health and nutrition awareness and facilitate access to treatment for illness. “The existence, training, support, and supervision of the community worker based in the community or operating from a nearby health facility are indispensable features of our community-based programs.”

To combat the negative health and nutritional impacts of STH infection in young children, RACSI has partnered with Vitamin Angels since 2014 to increase access to Albendazole for deworming. The effort is implemented during the bi-annual Maternal Newborn and Child Health Week (MNCHW) and ongoing services are coordinated with the government. To date, RACSI has distributed over 1.5 million doses of Albendazole to children 12-59 months.

The program has been well-received by communities and families alike, “Mothers are very happy with the deworming programme; they are informed and seeking for more services,” RACSI shared. “Community leaders collectively said, ‘we [are] glad and fortunate to have RACSI + VITAMIN ANGELS in our community giving our children and women access to quality health care.’ This is a rare privilege.”

“RACSI wants to use this opportunity to [say], we are deeply grateful, thank you for the fight against mortality and morbidity amongst women and children in our communities.”

[1] https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/world-population-prospects-2017.html

[2] https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/nigeria/

[3] https://apps.who.int/neglected_diseases/ntddata/sth/sth.html

[4] https://apps.who.int/neglected_diseases/ntddata/sth/sth.html

[5] https://apps.who.int/neglected_diseases/ntddata/sth/sth.html